While looking for the source of another Shaw quotation (to no avail), I came across this other gem. It is to be found in the "Preface on Doctors" to The Doctor's Dilemma. The quotation is often rephrased as in the title of this post, but it was originally written as two separate clauses in two consecutive sentences, as follows (my emphasis):

"…no doctor dare accuse another of malpractice.

He is not sure enough of his own opinion to ruin another man by it. He knows

that if such conduct were tolerated in his profession no doctor's livelihood or

reputation would be worth a year's purchase. I do not blame him: I would do the

same myself. But the effect of this state of things is to make the medical

profession a conspiracy to hide its own shortcomings. No doubt the same may be

said of all professions. They are all conspiracies against the laity; and I do

not suggest that the medical conspiracy is either better or worse than the

military conspiracy, the legal conspiracy, the sacerdotal conspiracy, the

pedagogic conspiracy, the royal and aristocratic conspiracy, the literary and

artistic conspiracy, and the innumerable industrial, commercial, and financial

conspiracies, from the trade unions to the great exchanges, which make up the

huge conflict which we call society. But it is less suspected."

|

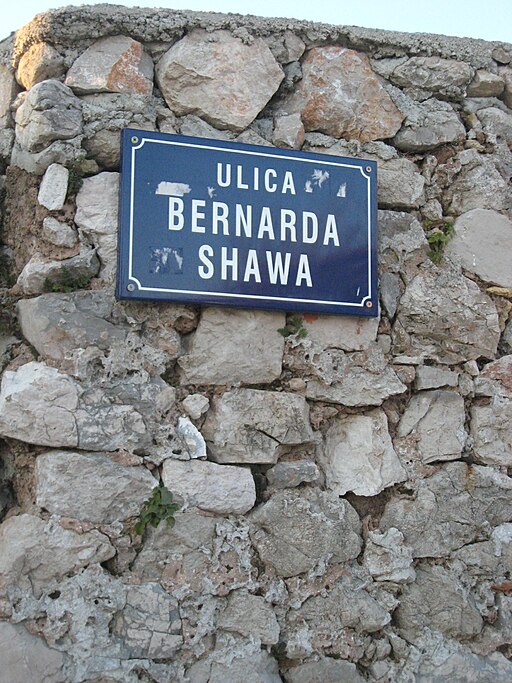

| Photograph of scene designed by Jo Mielziner for George Bernard Shaw's The Doctor's Dilemma. |

Some suggest that "conspiracies against the laities" is a common phrase in the English language and can be directly attributed to Bernard Shaw - although he may have been influenced by Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations.

If we start off with the latter claim, Smith's words are certainly similar to Shaw's general argument about the corporativism of all professions:

"People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for

merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends is a conspiracy against the

public, or in some contrivance to raise prices."

Although no definitive claims can be made as to the intertextual connection between Shaw's quotation and the passage in The Wealth of Nations, an economics expert like Shaw no wonder read Adam Smith's magnum opus thoroughly. In fact, we know he was very familiar with this treatise because, for example, in The Perfect Wagnerite, Shaw takes his ideal for a dramatic hero partially from The Wealth of Nations:

"The most inevitable dramatic conception, then,

of the nineteenth century, is that of a perfectly naive hero upsetting

religion, law and order in all directions, and establishing in their place the

unfettered action of Humanity doing exactly what it likes, and producing order

instead of confusion thereby because it likes to do what is necessary for the

good of the race. This conception, already incipient in Adam Smith's Wealth of

Nations, was certain at last to reach some great artist, and be embodied by him

in a masterpiece."

Also, Shaw reviewed some editions of The Wealth of Nations during his prolific career as a critic, so there's a chance at least the philosophical connection is there.

Regarding the status of "conspiracies against the laity" as a common phrase in relatively wide currency, we must take that with a pinch of salt. If, for example, we search for "conspiracy/ies against the laity" in any of the well-established text corpora available online, evidence of use of the phrase is scanty and almost always with a explicit mention to Bernard Shaw as the source. The GlowBe Corpus, for instance, retrieves 8 cases of the phrase - whether singular or plural - and all of them include Bernard Shaw in one way or another. Other corpora, like WebCorp, retrieve a few more occurrences, but many of them are collections of quotations. Once in a while, though, you find interesting articles like this one.

But the real question remains, why isn't this blog on the first page of Google for Bernard Shaw quotations? Is this some sort of "conspiracy against the laity?"

But the real question remains, why isn't this blog on the first page of Google for Bernard Shaw quotations? Is this some sort of "conspiracy against the laity?"